In 2014, Scotland held an independence referendum that resulted in Scots voting to remain part of the UK by a slim margin, with 55% against independence and 45% for. Since the vote, the political landscape across the UK has been in a state of constant volatility – largely incited by the 2016 Brexit referendum and the resulting exit from the EU. As a result, a revolving door of prime ministers at Westminster has ensued.

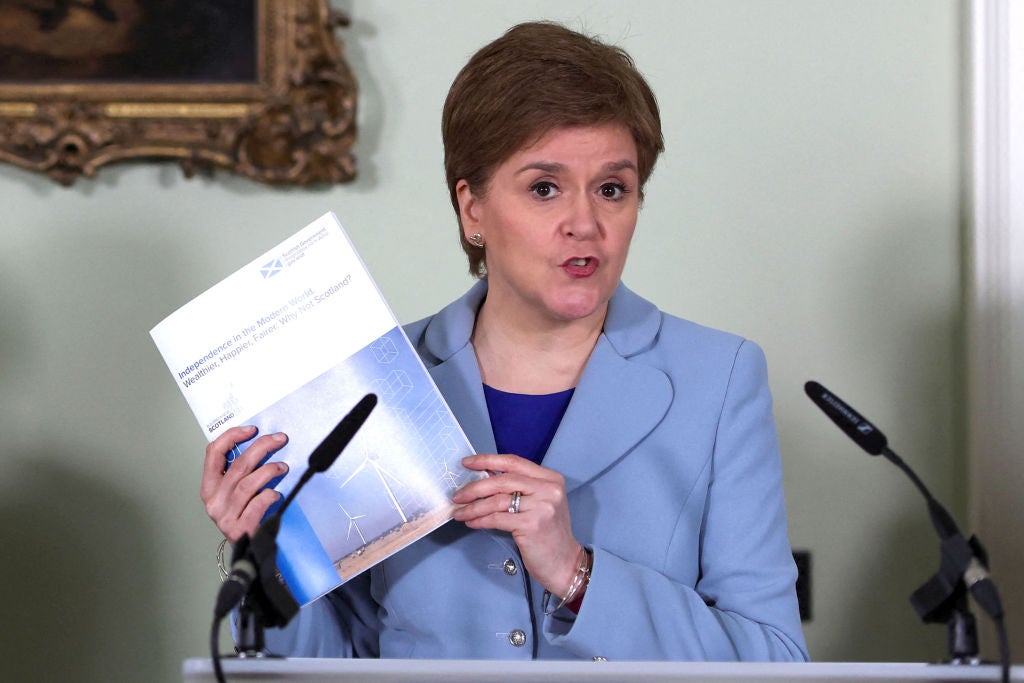

Throughout the continuous changes at Westminster and despite Scotland seeing electoral gains from the Green Party and challenger party Alba, the current First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, has held her position in Scotland since 2014 and seems unshakeable.

Sturgeon has presided as a custodian over the Scottish Parliament (better known as Holyrood) and the Scottish National Party (SNP), and with it their mandate to make Scotland an independent country. As Westminster readies itself to welcome the fourth UK prime minister since 2016, Sturgeon is laying the foundation for her independence swansong. After announcing an intention to hold a second independence referendum on 19 October 2023, the SNP has published a series of white papers setting out its intentions for an independent Scotland.

While Westminster has yet to agree to holding this referendum, it is clear that the debate over Scotland’s future within the union will only increase in volume over the remainder of 2022 and much of 2023. Many political commentators believe that the result of a second referendum will likely hinge on the economic argument, particularly as the UK is enduring a cost-of-living crisis.

Investment Monitor previously explored the potential cost of Scottish Independence for Scotland, but what of the rest of the UK? How will the absence of a Scottish economy and population impact Westminster’s purse strings? Amid a cost-of-living crisis, a Covid-19 strategy and coming to terms with the ramifications of Brexit, could losing Scotland be an expensive problem for England, Wales and Northern Ireland?

Is Scotland subsidising the UK?

In order to understand the potential cost of Scottish independence to the rest of the UK, it is important to understand the financial relationship between Westminster and Holyrood. There are conflicting stances on the reality of the financial standing between England and Scotland.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataIn 2019, the leader of the SNP in the House of Commons, Ian Blackford, made a contentious statement, stating: “UK government figures make it absolutely clear that Scotland has subsidised the rest of the UK in most of the last 40-year period.”

The comment was so widely debated that a fact checker from television station Channel 4 stepped in to shed some light on the claim. Essentially, Blackford’s argument hangs upon tax revenues being considerably higher per head in Scotland, so therefore Scots have paid more into the Westminster piggy bank. However, Channel 4 argued that the data behind this claim was unconvincing.

In 2019, the proof provided by the SNP was experimental data that came with a caveat: “Please use with caution as these statistics are particularly liable to revision as the data sources and methods used to produce them are developed.” They have not been revised since 2013.

Furthermore, the data provided ran for 32 years – from 1980 to 2012, with more recent years missing – making the 40 years claim unsupported. Yet, Channel 4 did report that the figures supported the argument that Scotland paid more in tax revenues per head every year from 1980 to 2012 when compared with the UK as a whole.

An oily issue

North Sea oil revenues were highlighted as the reason for these higher tax revenues. Oil is a bone of contention for economists trying to untangle Scotland’s value. Should independence come to fruition, the division of assets (including the oil within the North Sea) is a murky issue and there are arguments on either side of the border over who the oil and the resulting revenues truly belongs to.

The production of North Sea oil has been conducted overwhelmingly in Scotland, but can an ‘owner’ be identified for such an asset? There is some legal guidance on this issue, with the 1964 Continental Shelf Act ruling that the North Sea was under Scots law, which resulted in 90% of the UK’s oil being subject to Scottish jurisdiction.

If you accept this argument, when considering the 32 years of data provided by the SNP, then it is correct to say that during that time Scotland contributed more per capita than the UK average between 1980 and 2012.

However, despite Scotland supposedly holding jurisdiction over North Sea oil under the 1964 act, the private sale of the Cambo oil field in April 2022 – against Sturgeon’s wishes – and the extended gas field licence from Westminster act as an example of North Sea oil decisions being taken by Westminster, and not Holyrood.

If an independent Scotland were to take complete ownership and control of the North Sea oil and claim all resulting revenues, the rest of the UK would certainly suffer large losses in its oil and gas sectors, with only 5% of production left for the rest of the country, according to 2019 figures in the chart above.

Hey, big spenders

So the Scots have, at least for the majority of the time, been paying in more taxes than the rest of the UK since 1980, but these figures don't account for what the country takes out.

When looking at the 2020/21 public spending figures for Scotland, they must be considered under the condition that the impact of Covid-19 created an abnormal economic year with a drop in tax revenues, decreased economic activity and emergency measures undertaken by both Westminster and Holyrood governments.

With that in mind, the Scottish Government estimates that total public spending during 2020/21 was £99bn ($120.42bn), equivalent to £18,140 per head. This is higher than the UK average and for all regions apart from Northern Ireland. This therefore suggests that it is not true to say that Scotland is subsidising the rest of the UK.

However, the Scottish Government stated that through oil and gas revenues for 2020/21, the amount of tax raised can also be guessed at. It reported that approximately £63bn of North Sea oil-generated tax revenues were raised in that time period, which equals about £11,500 per head.

This narrows the gap between spending and taxation, but the outcome for 2020/21 still points to Scotland’s share of UK public spending being larger than its estimated share of tax revenues.

However, it is important to note that the combination of Covid-19 and volatile commodity prices made 2020/21 something of an outlier, and such an imbalance is not always present when it comes to Scottish public spending.

The Ashcroft Analysis – a report by the University of Strathclyde’s Professor Elizabeth Ashcroft – used experimental data to calculate the balance between public spending and taxation in Scotland in 2013. Looking at the same 32 years of data that Blackford referenced, Ashcroft found that public spending and tax revenue almost cancelled each other out, with Scotland paying just slightly more than it took out.

These figures should be taken with some level of scepticism, however, as is often the case when attempting to untangle the economic complexities of Scotland and the rest of the UK. For example, the data used had hypothetical qualifications around the potential of Scottish oil revenues and the surplus generated during the 1980s oil boom.

There is also no guarantee that if and when an independent Scotland is negotiating with Westminster that such contingencies will be considered and factored into calculations.

Hypotheticals aside, Scotland has had an increasing deficit over the past five years and any savings it may have left over from the 1980s oil boom are unlikely to offer a quick or simple solution.

Deciding on debt

The debate over Scottish independence inevitably deals with a lot of hypothetical issues. What happens to currency, to shared debt, to the banking system, to assets and to the pre-existing funding of projects? Many answers have been offered to these issues, but what will really happen cannot truly be known until independence happens (as was the case with the real-world impact of Brexit).

Should independence be voted for, lengthy negotiations would ensue, and neither camp on the prospective opposing sides of any debate can say with any certainty what the outcomes would be.

What can be taken as a likelihood, however, is that the cost-of-living crisis and the fraught communications between the SNP and the Conservative party mean that negotiations would be a fractious affair. This in turn could have an impact upon the future of trade between the newly estranged nations.

For the Scottish economy, the most important trading partner for exports is the rest of the UK. However, since the 2014 referendum Scotland’s exports to the rest of the UK have decreased slightly, with international trade showing a marginal increase.

However, this debate moves into hypothetical ground too. The continuing question lingering over any potential EU membership for Scotland (and with it access to the European Single Market, not to mention the prospect of a soft or hard border with the rest of the UK) makes it impossible to know what shape future trade relations would take.

It can be comfortably assumed, however, that the disruption in trade will have a ripple effect across legacy supply chains across the UK. When looking at the impact of Brexit on supply chains, it is clear that added borders and red tape cost businesses time and money on both sides of the divide.

Let’s not split the bill…

With many of the arguments over independence, past figures are touted to provide a glimpse of what a solo Scotland would look like, with hypotheticals built around this data that is cherry-picked to fit either bias. Yet many of Sturgeon’s arguments in favour of Scottish independence are future facing.

A key argument from the SNP in favour of independence is that Scotland would have the ability to avoid Westminster’s whims, and the bills that follow. A Scottish Government representative told Investment Monitor: “The UK economic model is persistently leading to outcomes for Scotland that fail to match its potential.”

The representative added that the first paper in SNP's Building a New Scotland series compared neighbouring comparable independent countries to Scotland and found that they tended to have higher GDP per capita and better productivity rates than the UK. It is insinuated then that free from Westminster’s control, Scotland could follow this small independent country blueprint and thrive.

If this profitable future were to materialise and Scotland were to become an independent nation with better productivity and a higher GDP per capita, this could harm trade in what is left of the UK.

A successful independent Scotland could reflect poorly on the rest of the UK, and England in particular. This would be even more problematic if Scotland did this as a member of the EU. The remaining UK would be something of a loner nation, surrounded by trade barriers and a common currency.

Scotland would also have an advantage as a member of the EU when it comes to talent flow. The freedom of movement that would come with this membership could enrich the country's talent pools, a route now closed to the rest of the UK. In the midst of labour shortages, this could be a very valuable asset for an independent Scotland.

However, it is not out of the question that this situation could work in Westminster's favour.

Given Scotland’s potential instability as a new state (given the teething troubles that any newly independent country experiences, and the potential break-up of the SNP once the nationalist raison d'être has been achieved), the rest of the UK could stand to benefit from investors looking to move south of the border in a bid to invest on more solid ground with better clarity on currency and trading regulations.

Messy divorce or couples counselling?

It is likely that there will be a second referendum on Scottish independence in the coming years, even if it doesn't happen in 2023. Those voting would, hopefully, feel better informed on what they are voting for when compared with 2014 too, given the added attention paid to the economic issues facing an independent Scotland, while the travails of the UK since the Brexit vote may also act as a reminder of what is at stake.

If the people of Scotland vote in favour of independence, there will be an economic cost to pay on both sides of the border, and at the very least unavoidable disruption that comes with the territory from such a divorce.

However, unlike Scotland, the people of England, Northern Ireland and Wales will likely have no say on whether or not they will be forced to pay that price. For Scots tired of being under Westminster's rule, that may act as karmic retribution, particularly after an unwanted EU exit (Scotland voted to remain in the bloc by a margin of 62% to 38%). Indeed, given the recent proclamation from UK prime ministerial candidate Liz Truss that Sturgeon is an "attention seeker" who should be ignored, any hopes of an amicable divorce, or even a dampening of the tension between the two sides of the independence debate ahead of any referendum, seem optimistic to say the least.