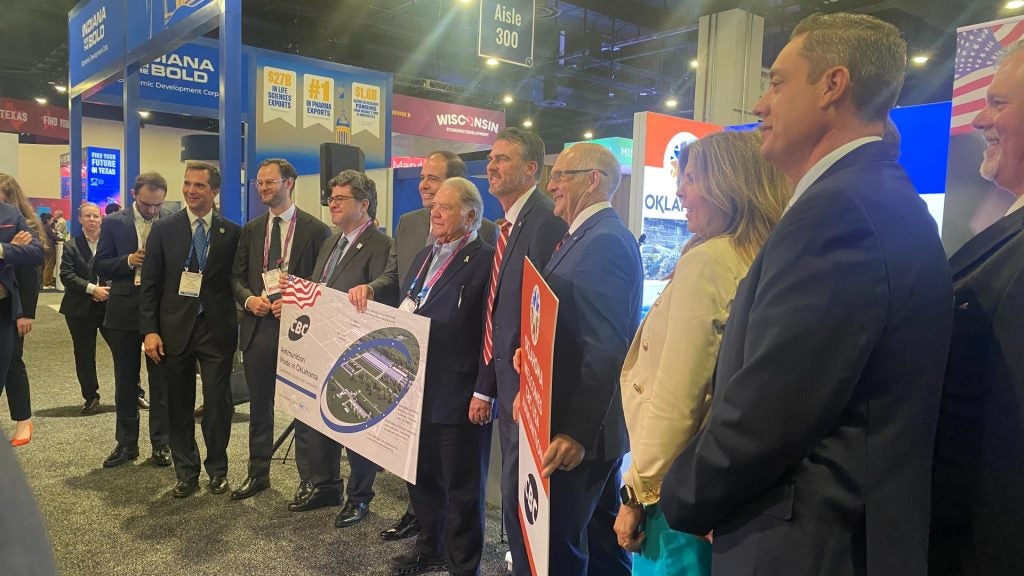

Last week, over 5,000 delegates gathered in a sprawling convention centre just outside Washington DC to answer one question: is the US still the most attractive foreign direct investment (FDI) destination in the world?

The SelectUSA Investment Summit, established in 2007, is the US’s most important event to promote FDI. It gathers international businesses, industry leaders, economic development organisations and representatives from all US states. This year’s event, however, took place against the backdrop of a US-initiated trade war.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Many versions of the US’s current FDI standing emerged during the few days Investment Monitor was present at the event, but one thing was clear: the uncertainty brought on by tariffs is causing many businesses to pause, delay and hope for the best while some multinationals with long-term horizons double down.

The plenary sessions that featured industry leaders and government representatives mainly focused on the positive and were mostly attended by country delegations.

They discussed US President Donald Trump’s America’s First Investment Policy and pressed the suggestions that now is the “perfect time to be investing in the US” (Barbara Humpton, CEO of Siemens Corporation) and that “there’s never been a better time to select the US than now” (Ola Källenius, Mercedes-Benz Group CEO). Mercedes-Benz has increased production of some models in the US to counter the tariffs.

One of the very few statements on the main stage that alluded to the tariff mayhem of the past few months came from Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer, who acknowledged that “trade policy is creating a lot of stress in industries all across our economies.” When a moderator asked Hyundai CEO José Muñoz whether his company has increased production in the US because of tariffs (the “elephant in the room”, the moderator called them), Muñoz gave a long answer about how his industry’s time horizons are so long they do not make decisions based on “incentives that come and go.” Some of Hyundai’s moves, such as starting a tariff task force in April and shifting some of its production to the US from Mexico, suggest a different reality to Muñoz’s unfazed answer.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe rest of the Summit (except some smaller panels) took place downstairs, in the exhibition hall, where investment promotion agencies and other organisations from across the US had their own booths. Here, for the majority of people that Investment Monitor spoke to, there was no downplaying the difficulties that businesses are facing, given the rapid changes to trade policy. While many are still eager to engage with the US market, many feel the need for some level of predictability before fully committing.

European American Chamber of Commerce executive director Fernanda Ceva, who had recently been in Germany conferring with companies interested in investing in the US, said: “The impression that we have is that everyone is holding up to decide something until they have more certainty. I see that they’re still interested in doing business with the US.”

According to a poll of 6,000 German companies conducted by the German Chamber of Commerce and Industry, only 19% of firms in Germany are planning to expand to the US. German investments in the US account for 12% of the country’s foreign investment.

Yvonne Bendinger-Rothschild, the executive director of the European American Chamber of Commerce New York, said: “The problem is more the uncertainty than the tariff itself […] We’re constantly going back and forth. If we saw there’s going to be a 10% tariff, then people can plan with it to do something and make forecasts […] If you think about it, that we have earnings reports that don’t have a forecast in them, I mean, that turns every economist’s stomach.”

Christopher Chung, the CEO of the Economic Development Partnership of North Carolina, echoed this sentiment.

“What we are hearing at this event is largely around, just tell us what the rules of the game are going to be and assure us that these are the rules that will be in place for a while, and they’re not going to change in two or three years, because that makes it really hard for these companies,” he said. “That kind of back and forth […] creates a little too much uncertainty, and that makes it hard for [companies] to push ahead with their decision.”

Signs of a slowdown?

Hours before the second day of the summit began, the first day when media would be allowed in, the US and China reached a major milestone in trade negotiations when they announced a tariff pause. The US would reduce its 145% tariff on Chinese goods to 30%, and China would reduce its 125% tariff to 10% for 90 days.

The pause was a welcome development for everyone, as it seems to signal that the pace of change is slowing down. Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt suggested it would “give them the time to really sit down and have cooler heads prevail.”

But others highlighted that the pause was just that, a pause.

“You’re seeing a little bit more certainty now that there’s going to be negotiations, but again, it’s a pause,” said Ed Brzytwa, vice president of International Trade at the Consumer Technology Association and a former official of the US Trade Representative’s Office. “The President himself confirmed that at the end of the 90 days, if China doesn’t cut a much more substantive deal, that the tariffs could come back on, maybe not all the way to 145% but certainly not as low as 30%.”

While some importers or inventors have stopped or delayed plans, businesses have also been trying to circumvent trade barriers through other means. The demand for bonded warehouses in the US, buildings where imports can be kept before payment of a duty, has surged since the tariff uncertainty began. Goods can be stored in bonded warehouses for up to five years. Shifting global supply chains, once seen as the best method to avoid being affected by US hostilities with China, has become a tougher path.

“Companies have been trying to reposition their supply chains out of China, but they’re facing tariffs of 46% in Vietnam, 32% in Taiwan and similarly high tariffs in Thailand, Japan and South Korea,” Brzytwa noted. “So, they’re being penalised for making the right decision.”

Whatever happens with the tariffs, the interdependence of the global economy with the US means decoupling is not an option. This dependence fares well for the North American country, because firms would rather wait out this period of uncertainty than leave the US and try to replace it with another market (an impossible task given that the US is the world’s largest consumer market). The same cannot be said for companies that are caught in a waiting game with no end in sight.

“Europe and the US are each other’s biggest trading partners, and no tariff is going to change that,” Bendinger-Rothschild explained. “What the tariffs are going to change is how we’re going to go about doing business with one another, but we’re not going to stop. You can’t replace either Europe for a US company or the US as a European. [Companies] have confidence in the economy, because the moment we have the most faint of good news, the market is shooting up.”

The cautious approach foreign firms are taking, even as tariff pauses have been put in place, shows the implications of the US’s loss of credibility on global business decisions.

Preparing for the new normal

While the 90 day pause with China has just begun, we are already a third of the way through the other 90-day tariff pause – the one that began a week after universal reciprocal tariffs were announced in April. This break is set to last until July, prompting countries to rush to make concessions and deals with the US. The deals being made during this period, however, are not true trade deals, according to Rothschild-Bendinger.

“A trade agreement is a comprehensive agreement where you have everybody give a little, take a little,” she highlighted. “A trade agreement is not selling somebody more soybeans.”

Given the uncertainty around what the tariffs will look like at the end of the pause, some officials this publication spoke to said their companies are accounting for that uncertainty by factoring a base tariff rate into their projections.

Huynh Thien Phu, business development specialist at Vietnam-based coconut water supplier Betrimex, said his firm is “accepting […] that it’s going to be around 10-15%. If it’s around 10%, let’s say 11%, then it’s okay. We already pay five. Adding another five wouldn’t hurt us as much; we can adapt to it. But, hopefully it’s not high, in the 40s.” Vietnam was hit with one of the highest tariff rates in April, at 46% and is currently in trade talks with the US.

Brent Omhdal, executive vice president for government affairs at Taiwanese semiconductor firm GlobalWafers, commented: “If you believe the news reports, the new normal is 10% tariffs, so I think businesses, including our industry, are adjusting.”

Even the US’s development of the artificial intelligence (AI) industry, which was heavily touted by speakers during the plenary sessions, could be slowed down by the tariffs because of the uncertainty around the price of inputs.

On tariffs affecting semiconductors, Omhdal said of GlobalWafers: “Being the only manufacturer of silicon here in the US at 300mm, you could benefit from the tariff in that way. At the same time, we need to actually import some substrates, even from our own company.” A few days after the conference, GlobalWafers announced a $4bn expansion in the US.

The semiconductor industry is also facing uncertainty from an ongoing government probe. In April, the Trump administration initiated an investigation into semiconductors under Section 232, which enables the president to restrict imports that threaten national security.

“With these investigations, they could impose a tariff of 25% or more […] on the finished good that has a semiconductor in it,” Brzytwa explained. “Technology products have many different types of inputs […] If there’s a tariff on the semiconductor or the printed circuit board or let’s just say the glass casing, it makes it much more difficult and expensive to manufacture that product in the US.”

Companies have long been interested in investing in the US. And, despite the uncertainty, they still are. But given the events of the past few months, the ability to confidently predict the economic conditions under which that investment might happen has practically disappeared. Most firms can do is stay agile, vigilant and ready to change course.

Christopher Chung told Investment Monitor about his meeting with the North American CEO of a big aerospace company. “We were talking afterwards, and he turned to his communications person, and basically his question was, have we heard anything from the White House in the past 30 minutes? He didn’t say it as a joke.”