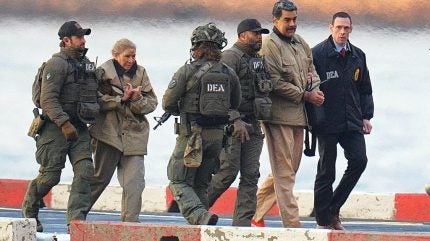

While tensions between Washington, DC, and Caracas had been building up for months—marked by the US bombing of small boats in the Caribbean and the seizing of Venezuelan oil tankers— few were bold enough to predict just how far US escalation would go. Even to most observers, the bombing of the Venezuelan capital (and other parts of the country) and the US capture of leader Nicolas Maduro and his wife, Celia Flores, by an elite special forces unit, seemed far-fetched.

Maduro was an autocratic leader, who presided over a period of significant economic decline, government repression, and a massive migratory exodus. To many Venezuelans, the images of him in handcuffs feel cathartic and like the start of the country’s long-awaited transition into democracy. Others, particularly those inside Venezuela, are fearful of what may come next, following Saturday’s unprecedented attacks. Some are also angry at the US invasion. While there is no official death count, it is understood that most of those killed were military targets. Civilian homes were also affected.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Countries around the world have denounced it as a flagrant violation of international law, but no further actions have been taken. The events and declarations that have since followed, from both Trump and Venezuelan officials, have in many ways created more questions than they have answered.

In the buildup to Saturday’s events, the Trump administration had focused on accusations that Venezuela is a central actor in the flow of narcotics into the US, particularly of fentanyl. This was used to justify the bombing of small boats in the Caribbean, which both Republicans and Democrats have condemned, and which the UN has characterised as “extrajudicial killings”.

While drugs do flow and are produced in Venezuela, the country’s role in the global drug trade has been described as “modest.” According to a March 2025 report from the State Department, Mexico was the only significant source of illicit fentanyl affecting the US in the preceding calendar year. Data from Colombia, the US and the UN also suggests that most of the cocaine that enters the US comes from routes in the Pacific, not the Caribbean.

However, during a press conference on Saturday (3 January), Trump honed in on Venezuela’s oil and on the US’s capacity to benefit from it. The country holds the largest proven oil reserves in the world, but production has plummeted in the past decade due to a combination of corruption, economic mismanagement, and US sanctions.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataAn oil revival?

“Venezuela currently only produces about a third of what they had ten years ago, before the collapse of oil prices,” Paul Hasselbrinck, senior energy analyst at GlobalData, tells Investment Monitor. According to GlobalData’s Upstream Database, in 2016 Venezuela produced just over 3 million barrels of oil a day (bpd). Today, this has plummeted to under 1 million bdp.

During the press conference, Trump said the US had a central role in building the country’s oil industry in its heyday, and that US companies would return to Venezuela, invest billions and rebuild the broken-down infrastructure. Francisco Monaldi, director of Latin American energy policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, told Bloomberg that rebuilding the oil industry would take years and cost upwards of $100bn.

The likelihood of this resurgence, Hasselbrinck notes, is complicated by many structural factors, such as a decimated infrastructure and poor governance. Even notable fields in the country, such as in Perla or Santa Barbara, are producing “well-below capacity, especially given the understanding of the reservoirs”. The type of oil present in Venezuela is also heavier, deeper underground, and harder to transport.

“The break-even prices for Venezuelan oil are much higher than equivalent oil produced elsewhere. And that’s despite a very depreciated currency,” Hasselbrinck says. “There is a generous scope to improve operational efficiency and have a competitive cost structure, but complex and long-tailed investments are necessary.”

“What that means —whether we believe Trump or not on the ability of the US to actually manage to first get [oil] licenses and second, pull the investment and actually be allowed in— is that in the short term, there isn’t the capacity to significantly increase production.”

“The only viable route via which production can increase is via Chevron’s existing license in Venezuela, which is obviously an exception, and that was used mostly as leverage and as a way to provide transparency to some of the oil exports that were coming out of Venezuela,” Hasselbrinck notes. Many more conditions would need to be in place for a surge in production, such as certainties regarding political stability and the ability to sell on an international market.

If production does increase via Chevron or ExxonMobil, which does not have a presence in Venezuela but has fields in neighbouring Guyana, it could face a less favourable market, given the “huge potential for oversupply in 2026.”

“What we know currently is that there is a lot of uncertainty. If the oil players are given assurances behind closed doors, then they’ll act differently to what we think they should do,” Hasselbrinck says.

Democracy, oil and spheres of influence

Trump’s focus on the country’s oil and lack of discussion about a democratic transition came as a disappointment. In 2024, the Venezuelan opposition is widely accepted to have won democratic elections, but no transition of power took place. The leader of the opposition, Maria Corina Machado, won the Nobel Peace Prize last month. She had been in hiding for over a year before her appearance in Oslo, Norway.

Trump, who has allied himself with Machado’s movement in the past, seemed to brush her aside during his remarks. “I think it would be very tough for her to be the leader […] She’s a very nice woman, but she doesn’t have the respect,” he said.

Trump and Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who is also a strong ally of Machado’s and a central figure in the operation, suggested that the US would work with Maduro’s Vice President Delcy Rodriguez. Rodriguez initially struck a defiant tone against the US, demanding the return of Maduro, but subsequent declarations have been more diplomatic. Trump said she would face a worse fate than Maduro “if she doesn’t do what’s right.”

During an interview with NBC News on Sunday (January 4), Rubio also said that the operation was about regaining influence in the Western hemisphere, countering Trump’s focus on the oil.

“We don’t need Venezuela’s oil. We have plenty of oil in the United States. What we’re not going to allow is for the oil industry in Venezuela to be controlled by adversaries of the United States […] This is the Western hemisphere, this is where we live, and we’re not going to allow [it] to be a base of operations for adversaries and rivals of the United States,” Rubio said, shedding some more light on the US’s intentions.

So, what is happening here? Regime change? An aggressive move to seize a battered oil industry? The upholding of the 2024 election results? Or, just more of the same dictatorial government, with a different person at the helm (whether this is Delcy Rodriguez or Donald Trump, is anyone’s guess)? During Maduro’s trial in New York, despite the shackles and the circumstances, he insisted that it was he who was still in charge. “I am still President,” he told the court.